I think before I switch into class/teacher mode and start using “we” I’ll say a couple of things about the way I work and how that fits into the broader picture of things with regard to this list of questions about sewing classes and design.

A lot of the time I get folks who are just starting out in this world with all of these ideas of what fashion or design is or should be that are either not my own experience or not correct at all. I’ve been working in design since who knows when and hosting sewing classes at my workroom since 2006. One of the things I have found along the way is that there is only so much information about process and structure of your business (YOU are your business, fyi) that anyone can give you. I mean everyone is going to have an opinion or notion of some sort – some of those will be useful to you, some of them won’t.

You, as a designer or creative person, should be thinking of your own direction. Regardless of what anyone tells you – including me. If some piece of advice doesn’t fit, or doesn’t seem to be right, then it just doesn’t and/or isn’t. You have to move on and up from it. This does not mean that you will succeed in this projection of yourself as you see it, but there is a price to pay for everything. You have to be willing to pay that price.

The clothing I design I don’t talk much about because for me that is something interesting and intimate between a designer and a client and I don’t want to have to rely on this perpetual cycle of promotion to make things work. I don’t fit in particularly well with the broader design community because of this, although I often respect and always understand what they are trying to do and why. So that should be taken into account as well. I don’t mind small showings, and let’s face it: runway fashion shows are SO. MUCH. FUN. but at the end of the day, none of that is really for me personally.

So I’d say keep all of that in mind – you are asking these questions of a guy who knows his way around a sewing machine, has drafted and designed for decades, and has built this really interesting life in a little corner of the sewing and design world that suits me perfectly but isn’t what other designers, manufacturers, or sewists would necessarily recognize as the pinnacle of success, luxury, and fame.

At the end of the day: The people who need to find you and who value what you bring to the table and into the world will find you whether you yell and scream and hashtag yourself to death on Instagram or not. Do. your. thing. The world may or may not catch up to it.

•••

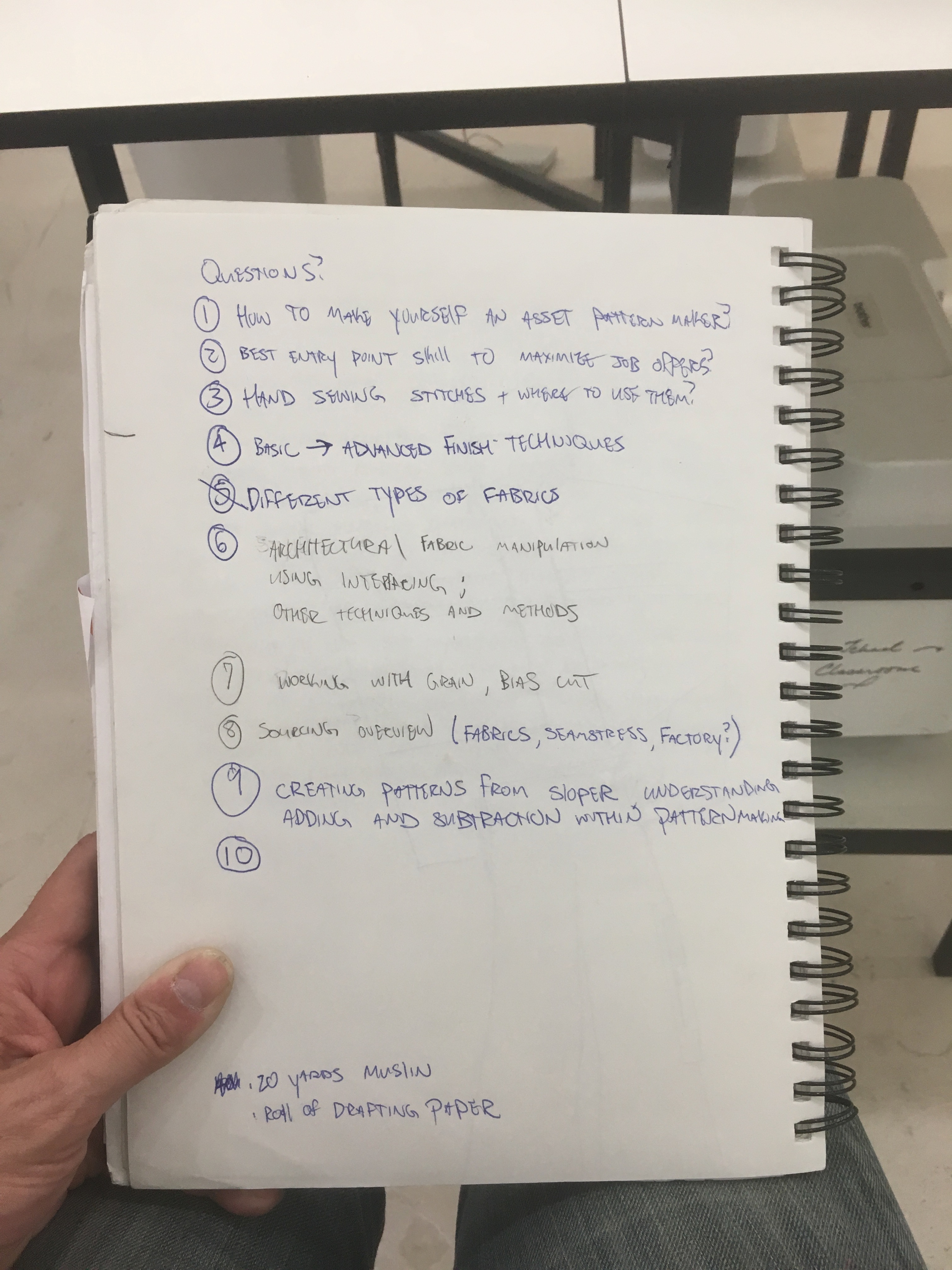

So Carson Lovett came to class the first day with a list of questions written out in his sketchbook. Like other design students and design student hopefuls, he wanted to get a bit of a leg up so that he started strong when he got to school the first semester. Perhaps we should break this down into a series, but we don’t do enough long-form writing on the blog anyway…

1. How to make yourself an asset patternmaker?

The best answer to this question is going to be in multiple sections:

• Know your craft in-and-out. You want to be able to draft things and be so familiar with grading that you can do it in your sleep. You want to be able to look at a sketch and come up with three or four ways that it could come together from the most efficient to the most decadent and how those do and do not overlap. Different people will have different motivations in hiring you; you do not want to produce a pattern for a bomber jacket that is so complicated it will take US$400 to manufacture if you have been hired by a local Instagram or brick and mortar designer who sells fast fashion for US$60. That is not a relationship that is going to work out, regardless of how good you are. Learn and understand pattenrmaking conventions with regard to marking, labeling, and specification sheets.

• Become known as someone who not only knows what they are doing but delivers on whatever you promise. This can be especially hard when you are in your 20s because things are so hectic and everything seems so desperate, but seriously: We’ve had more than a few people running small design businesses who wanted to learn to draft for themselves because the patterns they had made by an actual person credentialed in pattern design and pattern making were figuratively trash – and sometimes literally. We can think of four pattern makers offhand in Chicago who are worth their weight in gold. Their names are whispered and bits of paper with their emails are passed around like winning lottery tickets. It isn’t that those outside of the gold-standard folks aren’t good people or don’t know what they are doing – it is that some of them over-promise, over-commit, and then let folks down. The gold standard folks are the ones who come through and are honest with expectations and abilities.

There was one guy who showed up on our doorstep with the pieces of a bomber jacket pattern that he paid US$500 for someone to draft that were literally drafted on various old bedsheet percale scraps with a wide-bevel-point sharpie. Don’t be that patternmaker. Up until that point we had been recommending them as a competent drafter and patternmaker. Because they really are. But that was the end of that. And the pattern maker in question doesn’t even realize the chain of reactions to this one terrible job.

• Network. We aren’t great at this and don’t really love it, but use any alumni or internship connections you have if you are going to school for design and/or construction. Put things up on social media about what you are doing. Start an Instagram of your own patterns or work you are doing. Selfies of you drafting are fine, but people want to see the work if you are going the public route. If you are going to do look at me, it should be “look at me work” but even better is “look at these things I just brought into the world”

So know your craft, develop your eye, commit to realistic goals, and network – either overtly or covertly.

2. Best entry point skill to maximize job offers?

This is an interesting question because it makes us think in terms of corporate work and situations where you are applying for things. This has never been our bailiwick; most of our experience in design and sewing hasn’t been like that, but we’ve tailored this life so that it would never ever EVER be.

However! One of the things we would say is:

Learn. To. Sew.

Of course we would say this, but seriously:

Learn to sew and sew properly.

So many young designers, regardless of their design genius (and there are a ton of them), do not know how to sew or do not know how to sew well enough to pass any inspection. This is fine if you have backers, bankers, or financiers behind you or if you are willing to negotiate the dark night of the soul that is begging on kickstarter or gofundme to have your things made. We’ve never done this because we avoid debt; financial, professional, or existential debt makes us break out in a cold sweat. So learn to sew so that you can spend your money on sewing studio space, fabrics, and plane tickets when you need to travel for a potential job. There are a lot of small jobs and clients who will be happy to hire you if you can get to them. If you are saving and spending your money right, you can do this too.

Secondarily, we would again mention networking in all its various forms. In February we stumbled across a meme that said: “Hustle beats talent when talent doesn’t hustle”. This is exactly that. At the end of the day, most everything in any facet of design is just some variation on “eh…fine” with floating drifts of genius or terribleness in one direction or another. This has always been the way of the world in any profession anywhere. You overcome this by networking, force of personality, and work. The meme can be reversed to “When talent hustles it always beats hustle alone” but that isn’t as true as it should be.

So: Learn to sew well, network, and make sure the people who need to know you exist know it. Most of them will find you anyway, we believe, but still.

3. Hand sewing stitches and where to use them?

So if you are focusing on manufacturing and opening a boutique, there is little call for hand sewing unless you are talking about alterations. If you are going to get into tailoring (as opposed to alterations – these are properly understood not the same thing), then that is a different story altogether. In general, you need to know six basic stitches: running stitch, stab-stitch, backstitch, slipstitch, blind hem stitch, and the diagonal basting stitch. If you want to add to that, you can throw in the buttonhole stitch, blanket stitch, catch stitch (herringbone) stitch, cross-stitch, and the fagoting stitch.

Our basic advice here would be a comprehensive book of hand stitching like Handsewn. It will walk you through all of the stitches you will need throughout your sewing career in a basic sense and then, when you need to focus on the application of specific stitches you can use a tailor’s or dressmaker’s manual.

4. Basic to advanced finishing techniques?

5. Different types of fabrics?

6. Architectural/Fabric Manipulation; Using Interfacing; Other Techniques and Methods?

7. Working With Grain, Bias cut?

8. Sourcing Overview? (Fabric, Seamstress, Factory)?

9. Creating patterns from sloper – Understanding adding and subtraction within pattern making?

10. He left this blank, so we’ll just make something up and put words in his mouth…

And that is about that for this list of questions. We’ll pop in from time to time with more questions we get asked as they come to us…

In the mean time, Carson is finishing up his first year at xxx and in the meantime you can follow his design journey on his Instagram.